In Our Time - Common Sense Philosophy

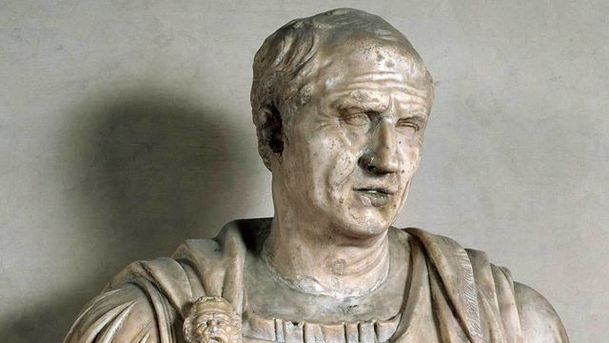

Melvyn Bragg looks at an unexpected philosophical subject - the philosophy of common sense. In the first century BC the Roman statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero claimed “There is no statement so absurd that no philosopher will make itâ€. Indeed, in the history of Western thought, philosophers have rarely been credited with having much common sense. In the 17th century Francis Bacon made a similar point when he wrote “Philosophers make imaginary laws for imaginary commonwealths, and their discourses are as the stars, which give little light because they are so highâ€. Samuel Johnson picked up the theme with characteristic pugnacity in 1751 declaring that “the public would suffer less present inconvenience from the banishment of philosophers than from the extinction of any common trade.†Philosophers, it seems, are as distinct from the common man as philosophy is from common sense. But as Samuel Johnson scribbled his pithy knockdown in the Rambler magazine, the greatest philosophers in Britain were locked in a dispute about the very thing he denied them: Common Sense. It was a dispute about the nature of knowledge and the individuality of man, from which we derive the idea of common sense today. The chief antagonists were a minister of the Scottish Church, Thomas Reid, and the bon-viveur darling of the Edinburg chattering classes, David Hume. It's a journey that also takes in Rene Descartes, Immanuel Kant, John Locke and some of the most profound questions about human knowledge we are capable of asking. With A C Grayling, Professor of Philosophy at Birkbeck, University of London; Melissa Lane, Senior University Lecturer in History at Cambridge University; Alexander Broadie, Professor of Logic and Rhetoric at the University of Glasgow.