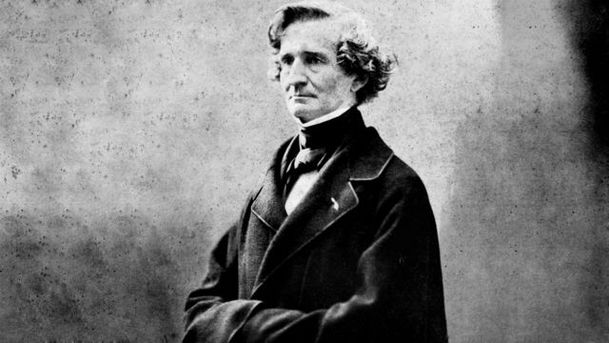

Composer of the Week - Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) - Episode 4

Donald Macleod explores the music of Hector Berlioz in conversation with Sir John Eliot Gardiner, in this Composer of the Week 'special' recorded at the celebrated conductor's Dorset farm. For Gardiner, Berlioz is perhaps the greatest of French composers, and he speaks with a lifetime's experience of studying and performing this remarkable music. Today's programme explores the poetic vein of death and melancholy running through Berlioz's output - on the face of it a somewhat gloomy line of enquiry, but in fact one that brings together an astonishing variety of reflections on mortality. On Berlioz's third attempt to win the coveted Prix de Rome in 1829, he was thought to be a shoo-in. In fact, he blew it. Rather than submitting a 'safe', conventional piece designed to impress the academic judges, he produced a highly original work that was held by the judiciary to 'betray dangerous tendencies'. That work was The Death of Cleopatra, and the prize was not awarded. Barely a decade later, Berlioz was considered sufficiently part of the French musical establishment to be commissioned to write music for a grand ceremony to mark the 10th anniversary of the July Revolution. In response he composed what he called his Grande Symphonie Funèbre et Triomphale, scored for a huge military band of 200 players. In the event, despite careful rehearsal the day before and the huge sound made by so many musicians, the noise of the crowds was such that hardly a note of the music was heard. The programme ends with Tristia - 'Sad Things', a title borrowed from Ovid. It's a triptych of reflective pieces including the well-known Death of Ophelia and the less well-known Funeral March for the Final Scene of Hamlet. Listeners of a nervous disposition should be alerted to the volley of musket fire at the climax of the piece - a musical counterpart to Fortinbras's speech: 'Go bid the soldiers' shoot!'.